“...I hoped people could relate to the subjects and see that their life’s work, all of our life’s work, is never finished. We leave a legacy. I hoped people would think, ‘What am I passionate about? What will my legacy be?’...”

In his film A Life's Work, director David Licata highlights the work and personal findings of a few people who have dedicated much of their lives towards ambitious projects. He explores themes of preservation, discovery, and creativity.

Here, Picture This Post (PTP) talks to David Licata (DL) about investigating deeply personal projects and conveying the emotional scale of a life’s work.

(PTP) Why did you want to make a film exploring the passions people feel about their work?

(DL) When I would give people the elevator pitch of A Life’s Work—it’s about people working on projects they might not complete in their lifetimes—many folks said something like, “That sounds like me and my garage.” I loved this response. It was, in a jokey way, exactly what I hoped an audience would take away after watching the film.

I hoped people could relate to the subjects and see that their life’s work, all of our life’s work, is never finished. We leave a legacy. I hoped people would think, “What am I passionate about? What will my legacy be?"

I wasn’t too concerned about losing the audience in a swamp of technical information.

I am not an expert in any of these fields, not by a long shot, and I let that be known to each subject from the beginning. So when I interviewed them if I understood the concept they were talking about, I was confident the audience would, too. And if I didn’t understand I’d ask the interviewee to explain it again until it made sense to me.

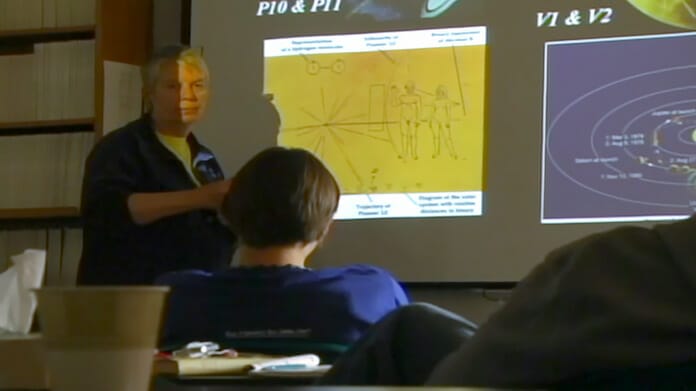

There are a couple of moments in the Tarter section where she is explaining something that might go over some people’s heads--in the scenes where she is addressing a bunch of undergrads studying the sciences—but with those scenes it is not important what she is saying but who she’s saying it to. She’s passing down her knowledge to future scientists. That’s what I hope people would get from those scenes, because that’s pretty much what the film is about. Knowledge and culture being passed down from one generation to the next.

What qualities did you want to highlight in the people you chose to profile in this film?

They are all very patient and level-headed. They don’t live and die with every success or setback. They don’t think, “Oh my god, I have to finish this series of buildings before I die!” They are more interested in getting their message out to as many people as possible before they die.

I went in thinking that each person discovered their passion somewhere between 7 – 10 years old. It was a notion I had before we started shooting. Michael Apted opened up every one of the 7 Up films with the Aristotle quote-- “Give me a child until he is seven and I will show you the man.” And I believed that wholeheartedly.

It turned out that this wasn’t true for each of them. Soleri said he had no great desire or passion to study architecture, but he got into it because he had to choose between a few subjects of study, and he didn’t really know why he chose it. And then he delivers one of my favorite lines, “It’s one of those divine mysteries.”

How did you go about depicting the deeply personal aspects of these projects, and make the subjects feel comfortable enough to talk about their life’s work?

Originally, I wanted to show [the subjects’] passion solely through images of their work—at the time I was very influenced by For All Mankind by Al Reinert. Reinert used footage from NASA of the Apollo space program and over it he laid voice over from several astronauts talking about their experiences. There are no talking heads and no lower thirds identifying the speaker so you never know if you’re hearing Neil Armstrong or Buzz Aldrin or Gene Cernan or any of the other Apollo astronauts. It’s a brilliant film—one of my favorite documentaries, and I thought I could pull off something similar. I went so far as to box myself into a corner and conducted the very first interview audio only.

But cinematographer Wolfgang Held made me see what a hare-brained idea this was. After all, we could conduct the interviews in front of the camera and if I really wanted to go that route, I could use only the audio.

But the idea of minimizing the talking heads was something I felt was important—so I tried to limit them to the facial or gestural expressions that were the most dramatic.

We conducted the interviews on the interviewee’s turf, and it was usually just the Director of Photography and myself—the smaller the crew the more relaxed the environment.

I didn’t ask any hard hitting or gotcha questions, but I had been told Soleri didn’t like being asked about why Arcosanti wasn’t completed. Still, I had to ask that, and I did so on one of the last days we shot him the first time we met him. I was dancing around the question and he knew it was coming, I could see it in his eyes and smile. So I asked with a lot of hems and haws and he said, “That’s the end of the interview,” half jokingly, and I laughed, because I thought it was funny and also because I was nervous. He answered, thank god, and we wound up interviewing him two more times.

In this film, there really was no reason to confront the interviewees, to deliberately make them uncomfortable. That being said, I did occasionally employ a technique I heard Werner Herzog uses. When the interviewee finished answering the question, I sometimes paused longer than seems natural before asking the next question. Often, given those few extra seconds, the interviewee would elaborate on their answer, or give an example, or say something contradictory, opening a door that I didn’t even know was there. It’s a handy thing to keep in mind, but it can be overused.

What tone did you want to strike in the film and what techniques did you use to achieve that effect – the score, the interview process, etc.?

From the beginning I wanted the film to be meditative. When you read a review and a film is called meditative that can be code for “bring your pillow because it’s slow and you’ll feel like you’ve spent a day in the theater.”

I didn’t want that, but I wanted it to be a quiet film, and I wanted to give the viewer some time and space to think about what they are hearing and luxuriate in what they are seeing. I don’t think there’s a shot that lasts less than five seconds, which by today’s standards, even for documentaries, is pretty long. There are a lot of quiet scenes, quiet bordering on silent. The camera is very still. And the film has an impressionistic look to it, pastel-like and nostalgic.

Ethereal-- That’s what I hoped for in the score.

The theme of the melody is that iconic phrase used by church bells to denote the time (The Westminster Quarters). The passing of time was something I wanted to show, and musically, that theme signified time better than just about anything. So there was music built around those notes.

I was influenced by Brian Eno and John Fahey, and I wanted to meld these two very different styles. The music shouldn’t call attention to itself, but work subconsciously, right, so I was very careful about not going too far with it, about keeping it simple, making it add to the mood of the shot and not detract from it.

All of the music was composed on the guitar, much of it altered thanks to many fine plugins, except for what you might call the climax of the film—the drone shot I mentioned. A grand piano accompanies the drone as we approach Arcosanti, playing that original theme.

By the way, the music is credited to Stella Josephson. That’s me. I felt like my name was all over the credits and it didn’t need to be in one more place.

How did you approach visually communicating the day-to-day tasks of your interview subjects?

I hope they visually show the subjects’ dedication despite the many difficulties they encounter, the patience they have to carry on, and the understanding they have that they are part of a long chain of scientists, builders, planters, and preservers of culture dating back centuries.

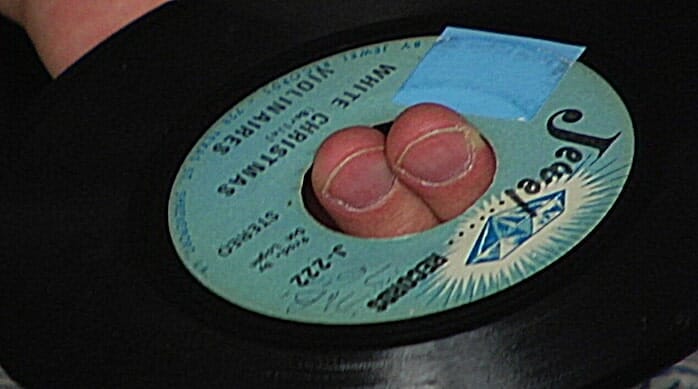

We tried to be as invisible and as unobtrusive as possible. This meant we didn’t stage anything (with the exception of Robert Darden entering the record store). I tried to be well out of sight and let the cinematographers—who are very experienced verité shooters—do their job. We didn’t put the camera right up in anyone’s face; I preferred to show them with their colleagues in long and medium shots when I could.

Oh, and I wore the drabbest, blandest clothes I own.

For one example—the last twenty minutes of the film shifts in tone a bit. We’ve come full circle with Soleri’s retirement and a new group of people are leading Arcosanti. To show that sense of renewal we opened the film up a little. In the very first shot of the film the camera tilts up from a dirt road in the desert to reveal. To capture that sense of renewal a drone approached Arcosanti from that same dirt road. Up to that point, everything was shot in standard definition, but with the drone onwards all the images were shot in HD and they are sharp and crisp, full-on high definition.

It’s easy to knock Arcosanti, but the above shots show that what’s there now was built with very little funding and by groups of eager apprentices and people who believed in the project and wanted to learn more about sustainable architecture.

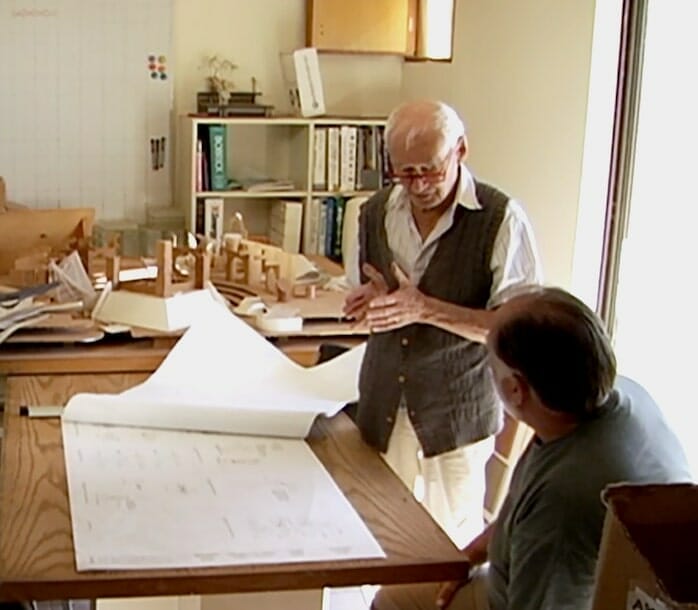

[The shots] convey the scale and scope of [the subjects’] work. To see the parcel of desert land that was bequeathed to Soleri for Arcosanti in the 60s, and the small scale model of what Arcosanti is planned to be and then crossfade to the current structure, should, I hope, give the viewer a sense of how far Arcosanti has come in the last 50 years, and how far it has to go.

Anything else you would like to tell Picture this Post readers?

There are extras on the film’s website that I like to think would be interesting to anyone who is curious about how documentaries are made, or how this one was made, anyway. I especially like the commentary with the cinematographers. That’s like Documentary Cinematography 101. I encourage anyone interested in becoming a filmmaker to spend 40 minutes watching it.

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

Nominate this for The Picture This Post BEST OF 2023???

Click Readers' Choice!

For more information visit the A Life's Work website. A Life's Work is available for streaming on Apple TV, Amazon Prime, and the First Run Features website.

Photos Courtesy of Happy Sisyphus Productions

Editor's Note: This story was initiated by former Cinema Content Curator Yash Pathak and completed by Mariama F Regaignon, Cinema Content Curator Summer 2023+

READ THE RELATED PICTURE THIS POST STORY--

Scottsdale Tour COSANTI (PAOLO SOLERI STUDIOS) Review – Giving Mother Nature Her Due

Read how filmmakers make their magic— in their own words. Read “FILMMAKERS SPOTLIGHT— Meet Filmmakers Picture This Post LOVES!” and watch this video for a story preview —

Click here to read more Picture This Post Review of Top Pick Documentaries and watch this video --

Picture This Post Documentary Reviews RoundUp --Our Top Picks